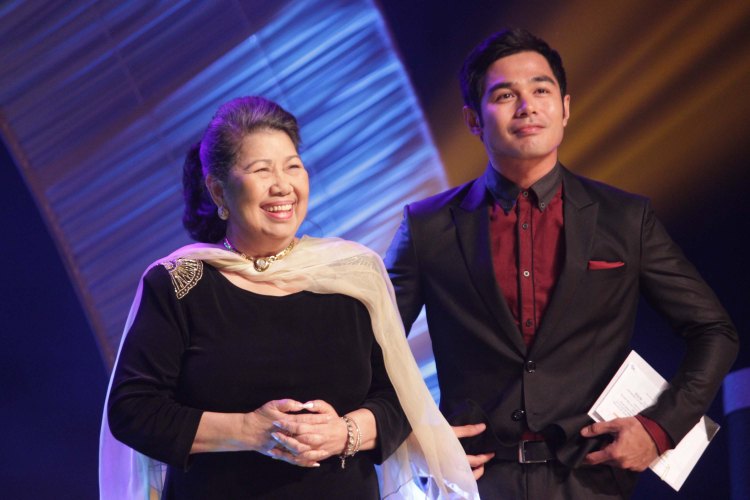

MARICHU VERA PEREZ – MACEDA

MARICHU VERA-PEREZ MACEDA: To the Film Studio Born

Butch Francisco

This year’s recipient of the Natatanging Gawad Urian for lifetime achievement is producer and industry leader Marichu Maceda. The Manunuri is giving the award to her for her long years of leadership in the movie industry, resulting in the institution of policies, programs and even agencies catering to the needs and interests of movie professionals.

Maceda was instrumental in the passage of Republic Act 9167, the law that created the Film Development Council of the Philippines, which formulates programs and grants incentives to improve the quality of Filipino movies. The council has formed the Cinema Evaluation Board, which evaluates and grades films submitted to it and depending on the ratings, grants them incentives.

To the film studio born, Maria Azucena “Marichu” Vera-Perez Maceda lives, eats, and breathes movies. After all, she belongs to the family that established (in 1937) the country’s biggest dream factory that was Sampaguita Pictures.

Growing up in the fabled Vera-Perez Gardens and having as playground the adjoining Sampaguita Compound that was used as setting in practically all their films, Marichu thought that life was one big movie. Playing with movie props, watching shoots right in their own house, and going through the rushes of their most recent movies—“I thought that was the normal way to live!”

For a playmate, she had no less than the biggest child star of the ’50s, Tessie Agana, whose Roberta literally rebuilt Sampaguita from the ashes after the studio was razed by fire in 1951. Agana, daughter of pre/post-war actress Linda Estrella, is Marichu’s second cousin and she remembers how the child star would only agree to shoot if she was given a whole Max’s Fried Chicken (“she ate only the wings…”). During shooting lulls, she and Tessie would play with the sticky leaves of the rubber trees that are still standing at the grounds of the Vera-Perez Gardens today.

One time, Marichu was given a brief appearance in a Carmen Rosales movie—as a flower girl in the wedding scene of Hele-Hele Bago Quiere.

In time, she was exposed to the other aspects of the film business and as early as age 10 or 11, she would be sent on weekends to the Life Theater (where Sampaguita movies were exhibited) to work as takilyera at the ticket booth. “Mabilis akong mag-sukli,” Marichu claims. She still remembers the admission prices back then (circa 1950s): P1.20 for orchestra, P1.80 for balcony, and P2.40 for loge.

Movies during that period had a 10-day run and Gloria Romero movies—so Marichu recalls—earned as much as P50,000 to P70,000 during the entire exhibition, huge compared to the LVN blockbusters that averaged only around P35,000.

Sometimes, Marichu would be made to sit as portera and collect tickets from movie patrons as they came in. This was when she learned her first lesson in the business—about how you have to watch closely every single detail of it.

On many occasions, she noticed how the designated portera would insert a ticket stub being handed by the moviegoer into a notebook instead of dropping it in the glass booth beside her. Eventually, Marichu discovered how those tickets inserted into the notebook were brought back to the takilyera to be resold—with the poor producer losing money in the process.

She remembers that lesson well when she started producing her own movies but—sigh—had yet to find to this day the perfect remedy to stop such petty thievery. As Marichu entered her teens, she continued learning more about the various aspects of film production and even distribution from the very lap of her father, the great star-builder/producer Dr. Jose Perez, who—in turn—gave her fabulous birthday theme parties at the Vera-Perez Gardens. One time, she had a red-and-white party. Then there was also a year when it was a White Christmas party, which—although it never snows in this country—was still in keeping with the usually nippy air that we have at every birthday of Marichu—Dec. 23.

At her debut party in 1960—so big, it was hailed as the showbiz event of the year—Dr. Jose Perez and his wife, Azucena or Mama Nene to Sampaguita folk, invited Manila’s eligible bachelors and one of them was 26-year-old Councilor Ernesto Maceda, who eventually became a congressman, a cabinet member, a Senator, and Marichu’s husband. Ironically, they didn’t even meet that evening “because there were so many people,” Marichu recalls.

It was the following week—at a Central Bank affair—that they were first formally introduced to each other. They fell in love and after a year, got married—when Marichu was only a semester away from completing her AB in Business Administration degree at Assumption.

Marriage requires any newly-wed to go through an adjustment period and this phase was particularly difficult for Marichu Maceda because, for one, she married quite young at 19. And there was the matter of her having been brought up practically in fantasyland—in a movie studio where a take two, three, four or more was allowed and where mistakes could be excised, edited and thrown in the cutting room floor. But this wasn’t possible in real life, except that Marichu didn’t know that—no thanks to her exposure from birth to the world of movies.

Local films then were in black and white and you could say the same thing about most Filipino screen characters in those days, who, too, came in black and white. No grays. Either they were good or they were bad. Marichu wasn’t even aware that there existed a middle-class. “I thought then that you were either rich or you were poor,” Marichu recalls.Given a sheltered life like that—“my marriage eventually collapsed,” she now looks back.

But even if she got separated from Ernie Maceda (their marriage was officially annulled only a few years ago), she has no regrets since the union, after all, produced five wonderful boys who all grew up to be responsible and intelligent men: Emmanuel, now vice president of the prestigious Bain & Co. in the US; Ernesto Jr., who is present dean of the College of Law of the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila; Erwin, an agriculturist; Edmond, an environmental engineer; and Edward, a Manila councilor.

And there were also a lot of happy moments during her marriage, particularly during the early part when she and Ernie had to live in Boston for one year while he took up his master’s in taxation at Harvard.

Upon their return to Manila in 1964, her father, Dr. Perez, immediately asked her to help him again with studio work this time with costumes and set design since Marichu knew how to draw and was good at it. She worked in tandem with an aunt, Nina Tarnate. In fashionable tunics, Marichu would ride the jeepney to Divisoria to buy fabric for her costumes and her favorite was cotton “because it didn’t look too shiny on screen.”

Designing costumes was actually quite complicated in those days of black and white movies when only the dance sequences were in color. Marichu had to be careful when choosing colors and even shades of fabric.

In black and white, red came out dark gray, navy blue became black, and if you wanted a nice shade of white, use pale yellow. She learned all that from her father and he was very happy with her costume designs.

One time, for Anong Ganda Mo! (1964), she played around with paper doilies and liberally applied those on the black gowns worn by Susan Roces and Gloria Romero. On screen, it had a beautiful lace-like effect and no one ever guessed that those were just, well, paper doilies used for tarts and pastries. Marichu said that she had fun designing costumes for Gloria and Susan because they never complained even if you made them come back several times for fittings. Gloria trusted her so much that in Show of Shows (1964), the movie queen, known for her vestal virgin image, even agreed although reluctantly to slip into a swimsuit that bared her legs… almost. Before the design could finally be completed, Gloria begged Marichu to please throw in a pair of fishnet stockings and some fringes “so that she doesn’t feel so naked.”

In between supervising fittings and attending to last-minute costume alterations, Marichu had to run to the sound studio to oversee the construction of sets since she was also involved in art direction. Although her father gave her a lot of pointers when it came to designing movie sets, Marichu was basically under the tutelage of Ben Resella, who was so brilliant, he eventually was absorbed by Hollywood where he did the set design of the Barbra Streisand musical, Hello, Dolly! which was directed by Gene Kelley.

It was while working as Sampaguita’s costume and set designer that Marichu realized the need for a movie to have a “total look.” “Watching local cowboy films in the ’60s and up to the ‘70s, naloloka ako sa mga spaghetti Western natin. The costumes were all so mixed-up,” she recalls with horror.

When she was setting up the Film Academy years later, she spent a lot of her time going from producer to producer, convincing them to support the establishment of a production designers’ guild and she succeeded. Today, we see the frults of her efforts. Some local films may still have costumes and sets that are so hopelessly lacking in coordination and even in continuity, but majority of Filipino movies these days already have production design, and we have to thank Marichu for that. On the part of the Manunuri ng Pelikulang Pilipino, as early as its inception in 1976, its members already recognized the importance of production design in a movie and while the Famas still called this category Best Art Direction, it was already Pinakamahusay na Disenyong Pamproduksyon even in the early staging of the Gawad Urian.

Marichu apparently already had the vision for the Philippine movie industry even then, except that she had to leave the film business for a decade (1965-75) in order to devote time to her husband, who had joined government service and later pursued higher political aspirations.

As a politician’s wife, Marichu Maceda had to learn how to organize, strategize and survive the rigorous campaign trail that required her to travel long distances (air, sea, and rough roads), wade in mud, and even learn dialects, especially when her politician-husband ran and won in the Senate. When father Dr. Perez died on July 28, 1975, however, Marichu had to return to the film business because, as the eldest among the children, she was made executive producer of Sampaguita and its sister company, VP Pictures.

Under her leadership, the company produced the following films: Tatlong Kasalanan; Mrs. Eva Fonda, 16; Ano ang Iyong Kasalanan, Rebecca Marasigan; Masikip, Maluwang, Paraisong Parisukat; Nananabik; Masarap, Masakit ang Umibig; Marupok, Mapusok, Maharot; Nakawin Natin ang Bawa’t Sandali; Dyesebel (with Alma Moreno); Rubia Servios (directed by Lino Brocka); and Garrote, Jai Alai King.

In 1979, she put up her own company, MVP and did three films: Stepsisters (with Lorna Tolentino and Rio Locsin), Pakawalan Mo Ako (with Vilma Santos) and Batch ’81 (with Mark Gil).

Of all the films she produced, Batch ’81 is closest to her heart. The idea of producing a film about fraternities came from her. It all started when she noticed how her son Edmond (then a high school junior at De La Salle) started wearing pajamas to bed when all along the boy would sleep in a more comfortable pair of shorts.

One evening, while her son was asleep, mother’s instinct drove her to check what the boy was hiding under those pajamas. To her horror, her son was black and blue all over. That very minute, she woke him up and made him confess where he got those bruises. It turned out that he joined a fraternity that was not recognized by the school. The very worried mother promptly got to the bottom of things and acted on the matter. That incident was what inspired her to produce a film about fraternities. She tossed the concept to Mike de Leon and he developed the story along with writers Clodualdo del Mundo Jr. and Racquel Villavicencio.

Batch ’81 started pre-production in late 1980, but was released only in November 1982. In between, Marichu had a series of battles with Mike de Leon and, later, with the censors. Oh, her fights with De Leon were monumental and lead star Mark Gil spent so much of his personal time trying to patch things up between them—until their next quarrel.

One time, Mike turned in his letter of resignation—which Marichu accepted. She later sent him a letter saying: “I will not even insult you by getting another director to finish this film because I AM finishing it myself.”

That threat—Marichu now laughs—was what made Mike de Leon come back. “What did I know about directing?” she laughs even harder. But she’s never one to make empty threats. At the height of the Mike de Leon walkout, she got on the phone with the late Fernando Poe Jr., asking the actor-director to teach her how to direct action movies.

Looking back, most of her fights with Mike stemmed from the fact that she was unable at times to deliver the logistics required to shoot Batch ’81 since she was then also in the middle of bankrolling Pakawalan Mo Ako. “Kasalanan ko din,” Marichu admits.

Batch ’81 may have bombed at the box-office, but it became a classic and is still one of the most sought-after movies in film festivals abroad. In 1982, it was shown at the Director’s Fortnight together with Kisapmata at the Cannes International Film Festival.

After Batch ’81, Marichu continued her role as industry leader, which started when she got involved with the Philippine Motion Pictures Producers Association or PMPPA.

When her father was still alive, local producers already found the need to band together in order to get better playdates for their movies. Initially, it was Ernie Maceda who represented Sampaguita. In 1976, however, Joseph Estrada and FPJ urged her to run for vice president. Three years later, she became PMPPA president and using half a million pesos she got from Mowelfund, she commissioned Carlos Valdes and Associates to make a study on the state of the Philippine motion picture industry and how its problems could be addressed.

This was how the Filipino Motion Picture Development Board or Film Board was created and under this umbrella organization were the Film Academy of the Philippines (and its 12 guilds), the Film Archives, the Film Fund, and the Board of Standards (upon the suggestion of Lino Brocka, Ishmael Bernal and other directors) that later became the Film Ratings Board (FRB) and which is now the Cinema Evaluation Board (CEB), the body that continues to decide which meritorious films should be give tax rebates.

When the Experimental Cinema of the Philippines (ECP) was later formed, it absorbed the Film Board, added that Alternative Cinema, but put the Film Academy under the jurisdiction of the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

Marichu was designated as the Academy’s Deputy Director General II and was made to head the Film Fund, which lent money to producers and helped them come up with good film projects.

In the early ’80s, when piracy started plaguing the movie industry, she got a call from Vic del Rosario, who was tipped off by Bobby Yang of the Greater Manila Theaters Association regarding the problem. Marichu marched to Malacañang, had a law signed by former President Ferdinand Marcos and the result was the Videogram Regulatory Board, which is now the Optical Media Board.

After EDSA 1, upon the creation of the Film Development Foundation of the Philippines, she gave full support to the scriptwriting contest and one of the winners there was Mary Ann Bautista’s Kasal, Kasali, Kasalo. Marichu knew the importance of the screenplay in the making of a good movie. Way back in Sampaguita, she assisted her father in choosing scripts for the company and, in fact, did a full script herself for Liberty Ilagan, one of the omnibus episodes in Umibig Ay Di Biro (1964). She co-wrote screenplays like Always in My Heart, My Blue Hawaii, A Gift of Love (all Nora Aunor-Tirso Cruz III starrers in 1971), and Just Married Do Not Disturb, a 1972 Gloria Romero-Juancho Gutierrez movie.

Sometime in 1996, Marichu brought industry members to the house of her brother-in-law, Speaker Jose de Venecia and this was how the International Film Festival Committee (IFFCOM) was formed. Now called the Film Development Council of the Philippines-Festival Committee, this body facilitates the exhibition of local movies in film festivals abroad (with help from the late Manunuri Hammy Sotto and Armida Siguion-Reyna, who also worked on the committee’s rules and regulations).

Now, Marichu is gathering ideas for another project that she thinks will greatly benefit the local movie industry. To the film studio born and after all this time, it is the industry that is her priority, the movie industry that she has lived most of her life for.

Back to Natatanging Gawad Urian